1940-1941

Everyone had been issued with Anderson bomb shelters, which were erected in the back gardens. Although there was hope that they would never be used, the dreaded air raids began in 1940 during the cold and wet weather. The first air raid warnings sent everyone down to the shelter, but water had seeped into ours and made everything feel damp.

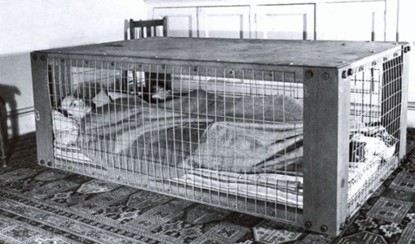

Worrying about the effect on the children’s health, Mum decided to stay in the house, so Dad dismantled the shelter and put half of it in the corner of our bedroom, arched over the beds. Whether it would have prevented us getting killed we never knew, because a new type of indoor shelter was decided upon by the government. This came in the form of a large table made of iron and steel, useful during the day for eating meals and as a refuge at night. Dad put some floor covering down inside and Mum put a tablecloth on top to hide the ugly iron work. You knew it if you accidentally cracked your leg against the hard metal. This was the Morrison shelter.[17]

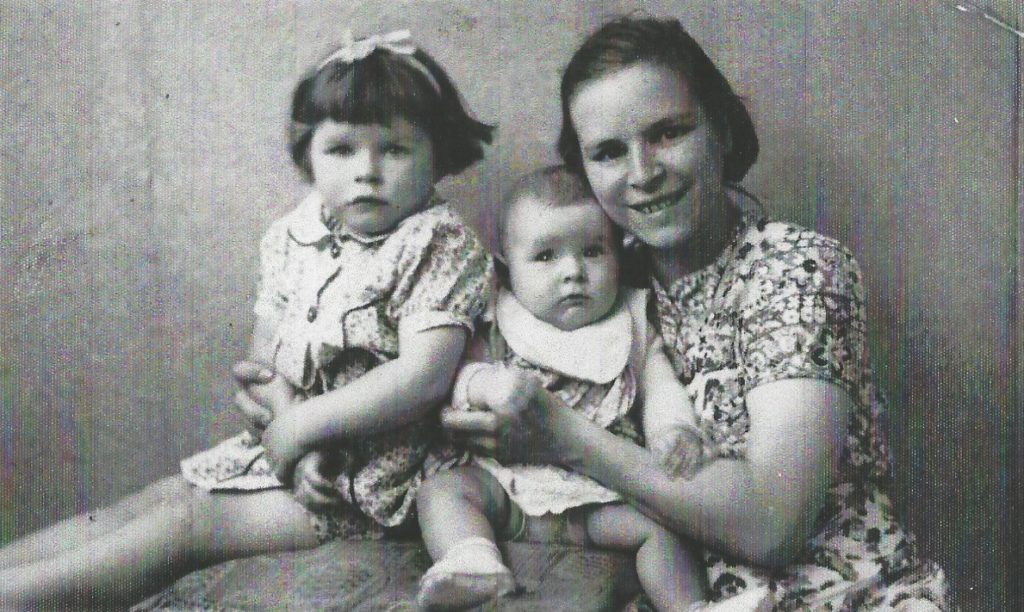

By now I was beginning to get up to things. Some of them I remember and others are what Mum told me. I do remember my sister’s pram and the blue wicker cot that she slept in, which had a round canopy threaded through with ribbon. One day, being excited about something or other, I leaned too far over the cot, which was on high legs with castors, causing it to tip over and almost throw my sister[18] out on a pile of blankets. A lucky escape, it’s a wonder she survived!

On another occasion, I tipped some brown iodine into her eyes, which being a strong antiseptic, burned, making the child scream. Mum flew with her to the doctors after rinsing her eyes out with warm water.

‘You’ve done right, Mother,’ the doctor said. ‘No harm done.’

Then to cap it all, I upset a bowl of water into the armchair when I was being readied for bed. I must have been a real horror.

One day, when Barbara was about two, Mum was getting ready to go shopping but had run back in the house to get her keys. While she wasn’t looking, I wheeled the pram away down the road. What a panic, as she caught up and stopped me just as I paused to cross the road. We could have both been knocked down.

About this time, my father was called up by the Army to serve in the Royal Artillery Regiment. His brothers were also called up, except Harry and Phil. Harry drove for London Transport as a bus driver, and Philip was not eighteen yet, but the others—Jim, Stanley and Len—went into the Army while Victor went into the Navy. Like us, it must have been a worry for poor Grandma Lawrence. She had a shelter in her garden, camouflaged by a rockery with a colourful display of flowers.

Now, I was old enough to remember some of the things that were happening. Mum’s sister Ada’s husband, Tom, once sat me on his knee and I still remember the funny antiseptic smell of his khaki uniform. Auntie Ada was pregnant at the time but Tom was sent out to the Middle East, so he was not to see his child until the end of the war when she was almost five years old.

Auntie Ada had a dangerous and difficult birth at my grandma’s in Hamilton Road with the added terror of the air raids, which did not help. She was a young woman, but of small build and the child was large. It was touch-and-go, but she pulled through and my cousin Violet was born. I was three at the time and my sister had been walking for just a year.

By now the raids were getting bad. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the summer evenings that were often spent with Grandma Lawrence at Summers Lane, the garden all full of flowers where I would sit making daisy chains on the lawn. The deckchairs would be out and sometimes we would have lemonade and crisps. Smelling the lovely scent of the garden, it would not seem that there was a war on, but then came twilight and the first chill of the evening.

Retreating to the house, it would not be long afterwards that we heard the dreaded sound, the wail of the air raid siren, sending a chill through every mother’s heart. A lot of young married women would feel alone because their husbands were away in the Army, and a few lucky ones would stay with their parents for company. If they had children, what would become of them? Suppose there was to be a direct hit? Suppose they died and the children were left alone? My mum was lucky in having the two old ladies upstairs, but in a way they too were her responsibility, one being deaf, the other blind.

When the sirens sounded, we were usually all asleep. I can always recall Mum shaking my shoulder to wake me, as she quickly got up and lit a small oil lamp with a match. We had electric light, but the dim glow of the lamp was safer because of the black-out, and the thick blinds at the window always had to be drawn so there was not even a chink of light showing outside. With blankets and pillows, we would go into the Morrison Shelter in the kitchen as Mum nervously lit herself a cigarette. To this day, the smell of matches still reminds me of that time, long ago.

Mrs Pearson and Mrs Barker, being elderly, declined having to crouch down and get underneath the table shelter, instead standing under the stairs where they stored their coal. The cupboard door would be open, as would the kitchen door, and Mum would stand with them smoking one cigarette after another.

After the sound of the siren had died away there would be silence, except for the sound of the old ladies shuffling and crunching about on the coal. Then I heard the noise of local gun fire from Sweets Nursery anti-aircraft battery at Whetstone. It always sounded as though someone was dropping large planks of wood from a great height. The aircraft, when they came, made a heavy droning sound, easily recognised as enemy aircraft. As a small child, I had slept through it inside the Morrison Shelter, but as I grew I became aware of the danger and felt a funny feeling in my stomach.

Our house was about half a mile from the main line railway from King’s Cross to Scotland, the local station being New Southgate where a lot of bombs fell. At the side of the railway line, just north of the station, was a large factory called Standard Telephones and Cables Ltd[19] and we think this was the target. A near hit would shake the ground and rattle every window in the house.

There was one bad raid, when a bomb fell close by and frightened us all! The blast blew the kitchen windows in and the frame as well. Mum said that the black-out curtains blew almost vertical, showering everything with glass. Fortunately, we were not hurt, but the bathroom window cracked and so did the toilet pan.

Just before a daytime raid, Mum had taken us to East Finchley for a visit to Grandma Trusler’s in Hamilton Road. We returned from Finchley to find Friern Barnet cordoned off, with air raid wardens stopping everyone going through. They asked Mum where we were going, so she explained we had got off the bus from Finchley and were on our way home to Goldsmith Road.

‘There’s a raid on and an unexploded landmine in Kennard Road,’ said the warden. ‘If you hurry and go round by Friern Barnet Road, you can pick up some things from your house and go straight to the church hall[20] in Bellevue Road in New Southgate.’

Out of breath, Mum arrived home to find the two old ladies upstairs in a flap, gathering their policies and valuables. It had started raining and the old pram was prepared with pillows, blankets and other essentials. My sister sat on the top as we all hurried to the church hall as fast as we could, with poor Mrs Barker and Mrs Pearson out of breath trying to keep dry under their umbrellas.

I remember the church hall well. It smelt musty. Young women were looking after the children, handing out paper and pencils to keep them occupied, which was when I first saw a desk pencil sharpener in use. A lady was winding the handle as the curly bits came out the end with the pencil sharpened to a fine point. The adults were given tea and biscuits by members of the Women’s Voluntary Services (WVS) and the children were given milk. Fortunately, we did not have to stay all night because the bomb disposal team soon had the landmine dismantled and we were able to go home.

In Goldsmith Road there were two public shelters, one at each end of the road. I remember on one occasion the air raid warden from our street bang loudly on the bedroom window. Mum went to the front door.

‘We are expecting a bad raid,’ he said. ‘For your own safety it would be best to use the street shelter tonight.’

We pulled on some warm outdoor clothing. The shelter was dim inside, and almost all the street seemed to be there, children crying about having to come out in the night. The only toilet was a tin bucket behind a curtain of sacking material. I was helped onto a high bunk.

‘Go to sleep,’ Mum whispered.

How could I go to sleep? By now the siren was wailing and me and my sister were very frightened. Women were talking in low tones and the smell of cigarette smoke, concrete and dust filled the air, but worst of all, a large black spider crept down the wall towards me. I screamed.

‘Mum, I want to go home!’

It was a bad raid, but Goldsmith Road escaped intact. We did not go back to the shelter in the street, or at least I do not remember going there again.

Probably during the very early part of the war, before the Blitz, as it was known, my mum recalled that once, while hanging washing in the garden, a loan enemy fighter plane flew across the back gardens of Goldsmith Road and fired its guns.

‘It flew very low towards me and opened-fire along the gardens. It scared the daylights out of me and I ran indoors. It was so low that I could see his face. He was grinning. I think he was just trying to frighten me.’

Leave a Reply