Rationing

At the onset of war, every family was issued with coloured ration books, beige for adults, blue for children over five and green for small children and babies. How Mum managed on our small rations is a mystery.

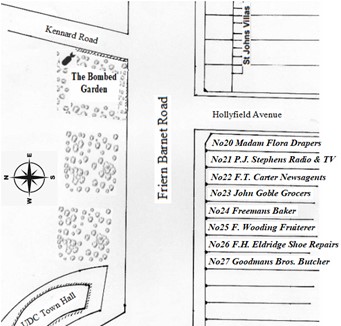

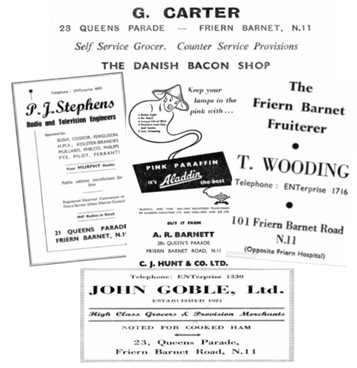

We were registered at Mr Goble’s grocery shop, which meant that we could only fetch our shopping from there. It stood opposite the town hall on Queen’s Parade,[28][29] always with a queue right outside, while inside, several assistants would be busy weighing up small pieces of cheese, butter, lard and margarine cut from large blocks on a marble shelf.

Amongst the shop’s fascinating aroma of ground coffee, fresh cheese and bacon, each portion was cut, weighed and carefully folded in greaseproof paper. Loose tea and sugar were weighed likewise and put into blue paper bags, while bacon was cut on a slicer which whizzed back and forth at great speed. Biscuits were in large tin boxes with glass tops, so you could see inside to choose. The only things that weren’t weighed and packed was tinned food.

At one time, we were only allowed an egg each a week. To supplement this, dried egg powder could be bought which Mum beat up with milk to make omelettes or to put into cakes. Lack of food was always of concern. There was a large sack of dog biscuits as you entered the shop, and once, Barbara and I could not resist having a nibble of one, but they tasted awful.

At the back of the shop was the Post Office, where large posters hung telling us to ‘Dig for Victory’[30] and ‘Save Saving Stamps’ to help the war effort.

Most families that were hard up used something called a provident cheque to make ends meet, which Mum was lucky enough to get. Using this method, we had new clothes and shoes bought for us from Madame Flora’s, the first shop on the corner of Hollyfield Avenue. A lady visited us every Saturday to collect money to gradually pay for the cheque, so that when one was paid for Mum would get a new one.

The trip to Madame Flora’s was always exciting, as we really valued a new pair of shoes, a coat or a dress. I once had a new wine-coloured crepe dress with a white Peter Pan collar, the same as Barbara. We also had a pair of brown crepe sandals and several pairs of white socks. With our mostly knitted cardigans, we felt smart when we went round to Grandma’s on a Sunday. Madame Flora had a good stock of coloured wools and patterns, which Mum would bring home to sit and knit with in the evenings, needles clicking away.

Next to Madame Flora’s was a radio shop, and next to that was Carter’s the Newsagent, the inside of which was musty and grim. Mr Carter, balding in a dark suit and crisp white collar, had bottled sweets on one side of the counter, newspapers on the other.

Goble’s was next, followed by Freeman’s the Baker’s. Poor Mum could not walk past without buying us a cake each, though I don’t think she could afford it. My very first ice cream cornet came from there, probably not real dairy ice cream, but the taste was wonderful. I am still reminded of it to this day whenever I am in a baker’s shop. The smell brings back the delightfulness of that particular ice cream.

Wooding Greengrocers was next. Sometimes the word would go round that they had some oranges and then a queue would form right down the street, but if you didn’t have a green ration book or young children you could be unlucky. When strawberries were once in season, Mr Wooding asked Mum if she fancied some with cream for tea. Although we were very hard up, he insisted.

‘Go on, here, have these at the bottom of the box’. He tipped them out into a bag and sold them to Mum for a shilling. How we enjoyed this luxury with tinned Nestlé cream.

After Wooding’s was the boot menders. They were always busy, because shoes had to last longer in those days, and it was a good job that most soles were made of leather because they were easily repaired. As we opened the shop door, a bell rang and the boot mender would stop with his hammer in mid air with a few nails sticking out of his mouth. Piles of shoes were stacked on a counter at the side, some already mended, some waiting for their turn. With blackened hands, he would take from us the shoes to be repaired, then continue hammering and cutting out leather. Sometimes a red-faced boy would be helping him.

Goodman’s Butchers was next door, with its sawdust covered floor and tiled walls with pictures of cows and sheep. Large posters advertising Benedict peas and Bovril adorned the walls. Arthur and George were the butchers, cheerful and jolly, smiling to the women queuing at the door, making wisecracks, nodding and winking as they chopped up scrag ends and other tiny portions of rationed meat. Once I laughed at Arthur and said something cheeky to him.

‘Here,’ he said, ‘In you go!’ He opened the door to the giant freezer and pretended he was going to shut me inside. After that I kept quiet in the butchers.

Win was the large comfortable woman who sat in the butcher’s kiosk.

‘How are you today, dear?’ she would ask, smiling and giving out change. ‘What a bad raid it was last night. I didn’t sleep a wink.’ Everyone knew Winnie and would tell her their troubles.

After Win left, a very young and smiling girl called Margaret took her place. It must have taken hours each night to put the curlers in her hair. She sat in the little kiosk like a queen, her head covered in brown curls, eyebrows plucked and drawn in with a pencil, her full lips pink with fresh lipstick. She stayed for about a year. There was gossip.

‘That Margaret at the butchers, she’s getting married. It had to be quick, you know? You know what I mean?’ Auntie May and Mum gave each other knowing looks. I had no idea what they meant at the time, but later we saw Margaret with a shiny pram and a very new baby, which I thought wonderful. I loved tiny babies.

Leave a Reply